Back to all Practitioner Perspectives

Ruth Morgan, Head Occupational Therapist

Children's Division, Central Manchester and Manchester Children's University Hospitals NHS Trust

Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA)

(Keller, J. et al, 2005a)

The COSA is a child-centred assessment that aims to capture young clients’ self-perceptions and values regarding their performance in everyday activities. This occupation-focused tool is one of several children’s assessments based on the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) that can be used to support and inform evidence based occupational therapy practice (Kielhofner 2002). The COSA compliments existing perceptual-motor and sensory assessments as it provides a broad overview of the child’s occupational preferences and skills.

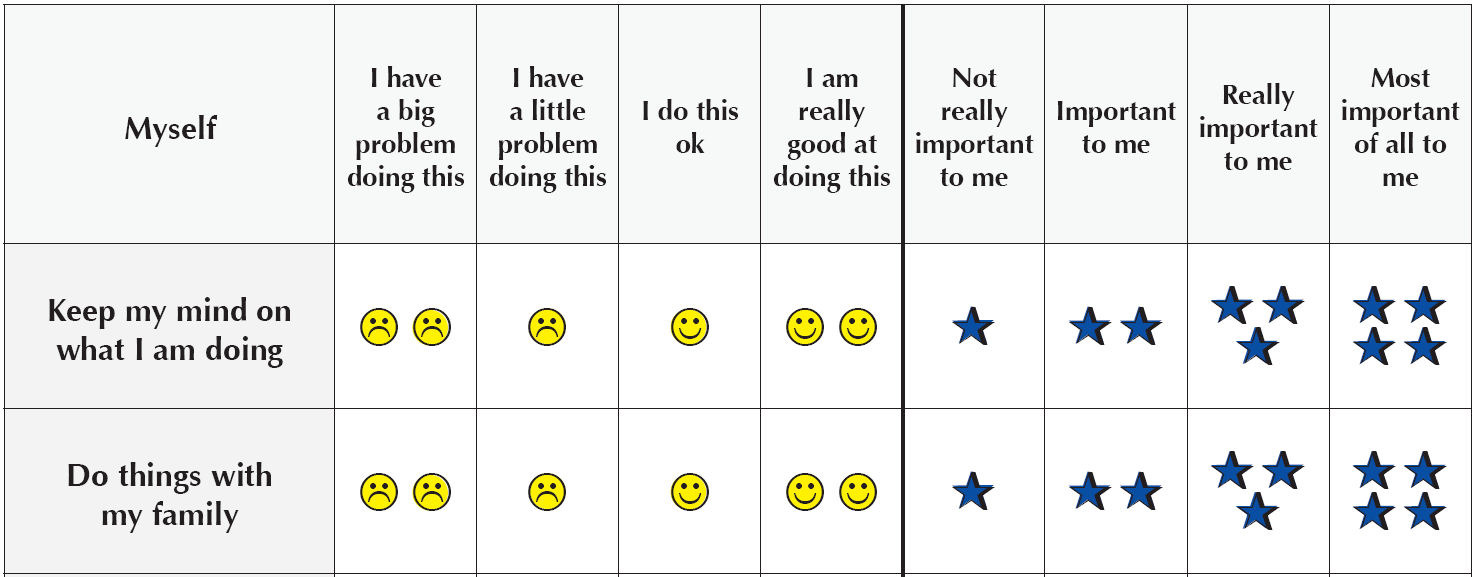

The COSA is a self-report that uses simple language, colour and symbols to accommodate children’s different ability levels and capture their point of view (see Figure 1). Two rating scales allow children and young persons to report how well they feel they perform a range of everyday activities and the importance of those activities. Activities on the COSA address occupations such as self care, socialising with others, and meeting school expectations. The administration procedures of the COSA may be modified to best facilitate children’s understanding of the activities and rating scales.

In my clinical practice I have used this assessment with children and young people with a wide range of occupational needs that were referred from the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service. Using the assessment has helped shift my focus from being skills-based to considering the wider influence of self-perception, motivation and contextual issues, and the impact that these issues may have on how children function. The tool has also given me a better understanding of a child’s perception of their skill level within a range of occupations and contexts. The COSA allows me to focus on the issues that are most important to the child, to identify their strengths that can be built on, and identify challenging areas that need to be addressed in therapy. I have found that focusing on the occupations that matter most to the child has helped young clients make choices, accept ownership and contribute to decision making when agreeing therapy goals. I have also used the COSA in collaboration with families to decide what areas should be prioritised in therapy or receive more in-depth assessment.

Using the COSA with teenagers and sharing the results with their parents has generated productive discussions between the parents, the young person, and the therapist. Reviewing the COSA responses reveals inconsistencies between the perceptions of the parents and the perceptions of the teenager, and provides each party with insight into the other’s perspective of the skills and difficulties the young person faces. The COSA also allows us to explore any differences in values family members may have for certain everyday activities. This process allows families to proactively identify potential conflict areas and facilitate positive communication about those areas. Some families seemed more able to identify positive strategies to manage potential problems once differences in perspectives and values were acknowledged. In some situations parents’ expectations of their child and therapy outcomes have initially been unrealistic. It has, however, been possible to use the COSA to negotiate clearly identified goals that the child has the potential and motivation to achieve.

Many therapists ask me if children can use the COSA accurately and appropriately. In my experience of using the assessment, most children pitch their responses fairly accurately - that is, children respond in a way that is aligned with the reports of others. Sometimes, children’s responses don’t match the perceptions of adults. However, on reflection, I realised this did not make the children’s responses any less valid as the issue being addressed is the child’s perceived competency. Some children tend to over-estimate their abilities, perhaps as part of a wider social awareness issue. These children may want to be seen as highly competent and able to do things in order to gain the approval of others. Other children seem to under-estimate their strengths and exaggerate their needs, which may reflect low self-esteem or a feeling of a lack of control over their life circumstances. These are important volitional issues, which the COSA can help identify that should be addressed in occupational therapy.

Currently, the MOHO Clearinghouse is building a database of patient assessments to further the development the COSA. Although two peer reviewed studies have already been published on the COSA (Keller et al., 2005b; Keller & Kielhofner, 2005), further research is needed. Therapists from all over the world have an opportunity to contribute to the development of this assessment by sending anonymous COSA data. For occupational therapists who are not active researchers, this is a unique opportunity to make a useful contribution to strengthening the existing knowledge and evidence base underpinning OT practice. I have found that engaging in the process is in itself a worthwhile continuing professional development activity. If you already use the COSA and are interested in sharing your clinical data with the MOHO Clearinghouse please write to Jessica: jkelle2@uic.edu.

Figure 1

References

Keller, J., Kafkes A., Basu, S, Federico, J., & Kielhofner, G. (2005a) A User’s Guide to Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA), The Model of Human Occupation Clearinghouse, Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, The University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois.

Keller, J., Kafkes, A, & Kielhofner, G. (2005b). Psychometric characteristics of the child occupational self assessment (COSA), part one: an initial examination of psychometric properties. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12(3), 118-127.

Keller, J., & Kielhofner, G. (2005). Psychometric characteristics of the child occupational self assessment (COSA), part two: Refining the psychometric properties. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 12, 147- 158.

Kielhofner, G., (2002) Model of Human Occupation: theory and application (3rd ed.). Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

Ruth Morgan, Head Occupational Therapist

Children's Division, Central Manchester and Manchester Children's University Hospitals NHS Trust

Download Full PDF