Introduction to IRM

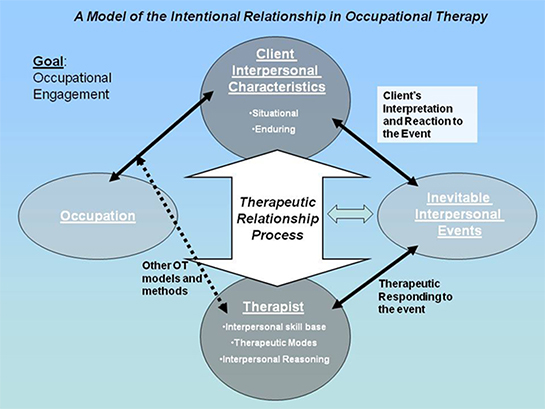

The Intentional Relationship Model describes a therapist's tasks and demands for establishing and sustaining a productive relationship with a client.

The Intentional Relationship Model guides occupational therapy practice by defining therapeutic use of self and thereby outlining an interpersonal reasoning process that therapists may apply when interacting with their clients.

Ten underlying principles of IRM

- Critical self-awareness is the key to intentional use of self

- Interpersonal self-discipline is fundamental to effective use of self

- It is necessary to keep head before heart

- Mindful empathy is required to know one's client

- It is important to continually develop one's interpersonal knowledge base

- Provided that they are flexibly and purely applied, a wide range of therapeutic modes can work and be utilized interchangeably in OT

- The client defines a successful relationship

- Activity focusing must be balanced with interpersonal focusing

- Application of the model must be informed by OT core values and ethics

- Cultural competency is central to practice

The therapeutic relationship

The therapeutic relationship is a socially defined and personally interpreted interactive process between the therapist and a client. During client-therapist interactions, it is the therapist's responsibility to foster

the therapeutic relationship and develop the client's occupational engagement. Every action, including verbal and nonverbal communication from the therapist is purposeful and aims to facilitate occupational engagement with the client.

The therapist

The therapist is not only delivering the technical aspects, but also responsible for facilitating and providing intentional therapeutic encounters with the client.

The AOTA Practice Framework outlines the use of self as skill within the scope of practice for occupational therapy practitioners.

The client

Each client is equipped with a unique set of experiences, challenges presently being faced, and an individual interpretation of any given situation.

In addition, each client has his or her own set of interpersonal characteristics that are interpreted by the therapist.

The 14 categories of interpersonal characteristics:

- Communication style: The client's approaches to a formally spoken or signed language.

- Tone of voice: A client's tone of voice may provide insight into his or her emotional state and reactions during an interaction.

- Body language: The client's postural state can indicate his or her current emotional state.

- Facial expression: Client's facial expressions can reveal their affect.

- Response to change or challenge: How the client responds when presented with change or challenge.

- Level of trust: Trust is built over the course of a therapeutic relationship; clients may have cautions or difficulty with trust.

- Need for control: The degree to which a client attempts to assume control over what is said and done during therapy.

- Approach to asserting needs: The client's ability to discuss what they want from the therapist openly and directly.

- Predisposition to giving feedback: The degree to which the client is comfortable with and predisposed toward appropriately providing feedback.

- Response to feedback: The client's level of comfort with receiving positive or constructive feedback and the clients' response to this feedback.

- Response to human diversity: The client's response to a wide range of differences that distinguish individuals from one another.

- Orientation toward relating: The level at which the client expects and prefers the therapeutic relationship to be conducted. This varies between clients.

- Preference for touch: The client's personal preference and interpretation of touch.

- Interpersonal reciprocity: The capacity of giving and sharing between client and the therapist.

The inevitable interpersonal events of therapy

The interpersonal events are described as naturally occurring communications, reactions, processes, tasks, or general circumstances that take place within the context of the client-therapist interaction.

These events typically consist of emotion, threat, and opportunity for the client and therapist with the potential of harming the client-therapist relationship if not handled appropriately.

It is the therapist's responsibility to navigate the inevitable interpersonal event with the client appropriately. The therapist's role is to maintain and foster the client-therapist relationship.

There are 12 categories of interpersonal event:

- Expression of strong emotion: The client's external displays of internal feelings that are shown with a level of intensity beyond usual cultural norms for interactions

- Intimate self-disclosure: The client's statements or stories that reveal something unobservable, private, or sensitive about the person making the disclosure

- Power dilemmas: The dilemma is characterized by an undeniable power difference between the client and the therapist

- Nonverbal cues: The client's communications that do not involve the use of formal language such as facial expression or body posture

- Verbal innuendos: Communication in which the client says something illusive or oblique that is meant to serve as a hint about a more direct communication

- Crisis points: An unanticipated, stressful events that cause clients to become distracted and/or that temporarily interfere with the clients' ability for occupational engagement

- Resistance and reluctance: Resistance is a client's passive or active refusal to participate in some or all aspects of therapy for reasons linked to the therapeutic relationship. Reluctance is disinclination toward some aspect of therapy for reasons outside the therapeutic relationship

- Boundary testing: Boundaries provide limitations and help the client to understand what to expect during therapy sessions; boundary testing is when a client behavior violates or asks the therapist to act in ways that are not part of the therapeutic relationship

- Empathetic breaks: Occur when a therapist fails to notice or understand a communication from a client or initiates a communication or behavior that is perceived by the client as hurtful or insensitive

- Emotionally charged therapy tasks and situations: Activities or circumstances that can lead clients to become overwhelmed or experience uncomfortable emotional reactions such as embarrassment, humiliation or shame

- Limitations of therapy: The client's restrictions on the available or possible services, time, resources or therapist actions

- Contextual inconsistencies: Any aspect of a client's interpersonal or physical environment that changes during the course of therapy

The modes

The Intentional Relationship model defines six modes of relating to a client that have been identified in occupational therapy practice.

Each therapist has their own preference based on his or her therapeutic use of self. While the therapist has a preference, the therapist should also attempt to best align the mode with the client's

interpersonal style in order to meet the needs of a client in a given moment.

- Advocating: Understanding that disability is a result of environmental barriers and as a therapist responding to physical, social, and environmental barriers that a client encounters.

- Collaborating: Making decisions jointly with the client and involving the client in reasoning, expectations, and having the client participate actively in these decisions.

- Empathizing: Bearing witness to and fully understanding a client's physical, psychological, interpersonal and emotional experience.

- Encouraging: Providing the client with hope, courage, and the will to explore or perform a given activity.

- Instructing: Educating the client in therapy and assume a teaching style in their interactions with the client.

- Problem-solving: Relying heavily on using reason and logic in their relationships with the client.